Table of Contents

Case Scenario

Mr. Clarke, a 45-year-old banking officer visited the physician complaining of generalized fatigue, muscle pain, and back pain for two years. He says his skin is too fragile to do any hard work without getting injured and he gets severely bruised with minor trauma. He asks the doctor for something to make him sleep well as he cannot sleep well.

He also has excessive thirst and leaves the bed several times at night to urinate. He is on Atorvastatin 20mg at night for hyperlipidemia for two years and he has self administered oral betamethasone 0.5mg every day for 20 years after a prescription for an episode of atopic dermatitis.

On examination, Mr. Clarke is plethoric and with a puffy face. He has a large abdomen with purple striations and wasted limbs. His skin is dry, loose, and very thin. Also, several bruises are seen on his knees and calves.

His blood pressure is 150/90 mmHg and his pulse rate is 65 bpm with normal heart sounds. The respiratory rate is 15 breaths per minute with no other respiratory abnormality. His random blood sugar level read 220 mg/dl.

Many of this patient’s symptoms are common sight for a GP, and some of them seem normal to his age, others being symptoms of specific diseases like diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. However, the clinical picture points towards the potentially ominous diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome.

Join us today for a comprehensive clinical case discussion on Cushing’s syndrome.

What is Cushing’s Syndrome?

Cushing’s Syndrome is a collection of symptoms and signs due to excess corticosteroids in the body. This can be a result of either too much production or excessive intake of corticosteroids for a long time.

The commonest cause for Cushing’s Syndrome is excessive usage of systemic corticosteroid medications. For example, oral prednisone, betamethasone, and dexamethasone. Other causes are ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) producing pituitary tumors, adrenal tumors, or other ectopic ACTH or corticosteroid secreting tumors. We can broadly divide these causes into a few categories.

- ACTH dependent

- Pituitary disease (Cushing’s Disease)

- Ectopic ACTH producing tumors

- Non – ACTH dependent

- Excessive therapeutic steroids

- Adrenal adenomas

- Adrenal carcinomas

All these causes ultimately result in high corticosteroid levels in our body,which affects our body’s immunity and metabolic functions, causing serious problems.

How Common is Cushing’s Syndrome?

The endogenous version of Cushing’s Syndrome is rare (0.7 to 2.4 per million). But iatrogenic Cushing’s, caused by prophylactic or therapeutic steroids, is relatively commoner as these drugs are commonly used to treat auto-immune diseases, allergies, and some cancers.

What will the Patient Complain About?

The patient will usually come complaining of non-specific symptoms like,

- Muscle pain

- Gaining weight and changing of appearance

- Weakness of limbs

- Low mood

- Loss of sleep

- Easy bruising

In addition, he may present with symptoms like polyurea, polydipsia indicating undiagnosed poor glycemic control.

What are the Signs to Look for?

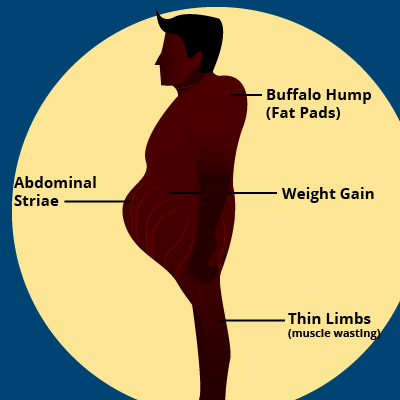

The commonest signs of Cushing’s Syndrome are,

- Plethora

- Moon face

- Weakness and wasting of proximal muscles

- Fat deposition at the posterior neck (buffalo hump)

- Thin skin and bruising

- Impaired glucose tolerance

- Hypertension

- Hirsutism

- Ankle edema

There are many other symptoms in addition to these, most of which are non-specific.

How do we Approach the Patient?

Just like in any other clinical scenario, we should follow the basic approach of history, examination, and investigations.

History

History gives us many important facts to arrive at a diagnosis. We need to ask the patient all the details about his illness, such as,

- the onset of the symptoms

- duration

- did all symptoms appear at once or did they develop in a specific sequence

- past history of medical conditions such as auto-immune diseases or allergies (maybe undergoing long term steroid therapy)

- previous history of surgeries (brain surgeries, adrenalectomy, etc.)

- family history of similar symptoms

- any drugs used for a long time

- food habits and lifestyle

This information collectively can lead us into a path of diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome while providing vital facts to find the cause.

Examination

We need to do a thorough physical examination of the patient to identify whether there are any signs mentioned before. Heart rate, any abnormalities of heart sounds, and blood pressure are important examination findings to assess the cardiovascular involvement. In addition, we should look for any signs of complications caused by pathophysiological changes of Cushing’s syndrome, such as renal and ocular involvement of hyperglycemia, signs of hypercholesterolemia, etc.

Investigations

Investigations can be categorized into three.

- Investigations for diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome

- Investigations to find the cause of Cushing’s syndrome

- Investigations for diagnosing the complications of Cushing’s syndrome

Investigations for Cushing’s syndrome are based on the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis and the circadian variation of secretion of Corticotrophin Releasing Hormone (CRH), ACTH, and cortisol. Commonly used tests are Urine Free Cortisol (UFC), 1mg Dexamethasone stress test, and late-night salivary cortisol tests. If there is a high clinical suspicion even after these tests are normal, we might need to go for more advanced tests such as insulin stress test, CRH tests, and desmopressin stimulation tests.

To find the cause, we may need advanced biochemical tests such as serum ACTH, CRH tests, and radiological investigations such as MRI, ultrasound scans, and X-rays.

Then, to assess the complications and progression of Cushing’s syndrome we can use basic laboratory investigations such as Fasting Blood Glucose (FBG), Lipid Profile, and radiological investigations such as plain radiographs of bones and DEXA scan to assess bone density.

How to Arrive at a Diagnosis?

As we now know the basics of Cushing’s disease and the approach to a patient who has the symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome, we can construct the path to arrive at a diagnosis. For that, let’s focus on what could be the differential diagnoses of these symptoms.

What are the differential diagnoses?

The symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome are non-specific. Therefore, the patient may complain of a variety of symptoms and each symptom can lead us on a different path. For example, the patient may tell us of polydipsia and polyurea, and when we check for RBS, it is high. Then we may diagnose the patient’s condition as impaired glucose tolerance and treat only that. Thus, if only we take an extensive history and perform a thorough examination, we will find the true underlying condition.

In addition, conditions such as morbid obesity, corticosteroid resistance, pregnancy, and psychiatric conditions such as depression may lead to high serum cortisol levels and we need to keep these in mind when interpreting biochemical test reports.

Finding the Underlying Cause

We can arrive at the diagnosis of Cushing’s disease with positive clinical findings (signs and symptoms mentioned above) combined with positive biochemical tests mentioned earlier. Then we need to figure out what has caused it.

As we know, the commonest cause for Cushing’s syndrome is exogenous steroids. Therefore, we need to review the drug history of the patient and check whether he or she is taking steroids. If so, we can omit steroids if possible, and check whether the condition is settling and serum cortisol is stabilizing. If not, we may need to investigate further.

Cushing’s syndrome can be ACTH dependent or ACTH independent. First, we need to figure out what category our patient belongs to. For that, we can do serum ACTH levels. If it is low (10ng/L) we can rule out ACTH-dependent disease and we need to find out a focus of corticosteroid production within the patient, such as adrenal adenoma, adrenal carcinoma, and adrenal hyperplasia. For this, radiological investigations such as CT, MRI are useful.

If it is significantly high, we need to suspect ACTH-dependent disease and we need to find the source of high ACTH secretion. For this, imaging methods like MRI-pituitary, CT chest, and abdomen may be useful. In addition, tests such as high-dose dexamethasone suppression tests are useful to identify whether the focus is in the pituitary or in an ectopic focus. In locating ectopic lesions, radioactive isotope imaging may be helpful.

What should we do about complications?

Usually, these patients present with complications of Cushing’s syndrome such as hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, reduced bone density. Therefore, we have to diagnose these conditions by using appropriate investigations and treat them. Most of the time, these conditions may resolve by resolving Cushing’s syndrome. Therefore, we should review these complications again after resolving Cushing’s syndrome and make treatment plans accordingly.

How do we Manage a Patient with Cushing’s Syndrome?

This is the most important part as untreated patients can have serious complications such as myocardial infarction, venous thromboembolism, cardiac failure, and severe infections with significant morbidity and mortality. Therefore, let’s discuss how to work out a management plan for a patient with Cushing’s syndrome.

The first goal of treatment should be to relieve the underying cause. As the commonest cause is exogenous steroids, we can modify the current steroid treatment and taper it off and review the condition. This may not be an option for a person with a disease or condition that needs steroid therapy. In this case, we may have to discuss with the relevant specialist to come to a favorable treatment plan for the patient.

If there is an endogenous cause for elevated cortisol levels, we may need a unique approach depending on the cause. The management can be broadly divided into medical and surgical.

Medical management,which comes first, is aimed at bringing down serum cortisol levels to the normal range of 150-300nmol/L during the daytime. Metyrapone is the preferred first-line drug. It acts by inhibiting the 11β-hydroxylase enzyme of steroid synthesis. Other drugs are Ketoconazole, Aminoglutethimide, and trilostane. Etomidate infusion can be used in resistant cases. High cortisol levels in a patient can cause significant complications during surgical procedures. Therefore, we need to control the cortisol levels of the patient before surgery.

We can use surgery as a definitive treatment in most cases by removing the lesion which is secreting excessive ACTH or steroids. Pituitary adenectomy or resection of adrenal lesions usually resolve the condition. We can add radiotherapy and chemotherapy to increase the effectiveness of the surgery. Also, bilateral adrenalectomy can be done to resolve Cushing’s syndrome if all the other treatment options fail.

While we are providing the definitive treatment, we should treat the complications too. Most of the time, they will be resolved but sometimes, complications may prevail even after successful treatment of Cushing’s syndrome. Therefore, thorough follow-up should be done in every patient even after seemingly successful treatment.

How do we Prevent Cushing’s?

We know that Cushing’s syndrome is rare. Therefore, extensive screening programs for it are not effective considering the cost. But, we can screen high-risk individuals such as patients on steroid therapy, patients with known pituitary and adrenal tumors, and people who have a family history of endogenous Cushing’s syndrome.

The most important step in prevention is health education. We need to educate patients who are taking steroids for a long time about this condition and encourage them to be vigilant about symptoms and seek medical care immediately if any symptoms appear. In addition, we need to educate the other high-risk groups mentioned above. The doctors also should be vigilant about this condition, especially when prescribing long-term steroid courses.

Let’s Get Back to our Patient…

So, after knowing the basics of Cushing’s syndrome, let’s consider what we can do about our patient.

Let’s go through the history first. We can identify a collection of symptoms that draw our attention to Cushing’s syndrome. In addition, Mr. Clarke has a history of long-term steroid use. Also, his symptoms suggest that he is suffering from hyperglycemia and the RBS confirms it. The most important fact of the history is the long-term steroid intake.

On examination, a set of signs indicative of Cushing’s were identified. Puffy face, central obesity, proximal muscle wasting, thin skin, and hypertension are more prominent of these.

So, the first step of our management is explaining the condition to the patient. He needs to know what has caused the problem, how to treat it, and the importance of adhering to the management plan.

Then, we need to reduce his steroid intake gradually, as a rapid reduction may have significant complications such as hypotension. We can switch him to a less potent steroid such as oral hydrocortisone or prednisone. Then we can taper it off gradually.

After stopping steroid intake, we can assess whether his serum cortisol levels have normalized by doing a serum cortisol assay. Then we can follow him up gradually until his symptoms disappear.

This patient has hypertension and hyperglycemia. Therefore, we need to advise him on lifestyle modifications such as a low glycemic index diet, reduction of salt intake, exercise to control these problems. If lifestyle modifications are not enough to obtain sufficient control, we can add pharmacotherapy such as oral hypoglycemic agents (E.g. Metformin, Glibenclamide) and angiotensin receptor blockers (E.g. Losartan) to control hyperglycemia and hypertension respectively. We may need to do a lipid profile to assess his serum lipid levels and adjust his drugs (Atorvastatin) accordingly.

His bone density should be assessed as reduced density may lead to pathological fractures. Plain radiographs of his vertebral column may provide a rudimentary idea of his bone density. We might need to add Calcium and vitamin D supplements to improve bone mineralization. If there is any suspicion of osteoporosis, we can refer him for a DEXA scan to diagnose it.

After addressing all his problems and complications, we can advise him to return for a follow-up after four-six weeks to assess his condition. If the condition has improved, we can continue the same treatment plan and assess the complications and modify treatment given for complications.

If his symptoms persist or serum cortisol levels are abnormally high even after withdrawal of steroids, we may have to look for a cause of endogenous Cushing’s. This will need extensive investigations as we discussed in finding the cause section to arrive at a diagnosis.

In Conclusion,

Cushing’s syndrome a condition caused by abnormally high serum corticosteroid with significant complications and has a very poor prognosis if left untreated. As the symptoms and signs are unspecific, you need to have a good clinical suspicion to identify the condition. If diagnosed early, we can cure it with minimal complications by using medications, surgical interventions, and lifestyle modifications.

References

- Kumar & Clark’s Clinical Medicine, Prof. D. P. J. Kumar, M. L. Clark, A. Feather, D, Randall, M. Waterhouse – Edition 10

- Nieman, L. K., Biller, B. M. K., Findling, J. W., Newell-Price, J., Savage, M. O., Stewart, P. M., & Montori, V. M. (2008). The Diagnosis of Cushing’s Syndrome: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 93(5), 1526–1540. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2008-0125