Table of Contents

First Things First: Definition of watershed infarction

When you think of the word watershed, what comes to mind? The literal meaning of watershed is a ridge of land which separates water flowing to different areas like oceans, rivers, ponds and basins. So, you may wonder why on earth such a ridge exists inside our heads! Think of it this way, if we consider the “water” to be blood instead, and these so-called “ridges” to be the gyri in our brains, this definition becomes a perfect metaphor.

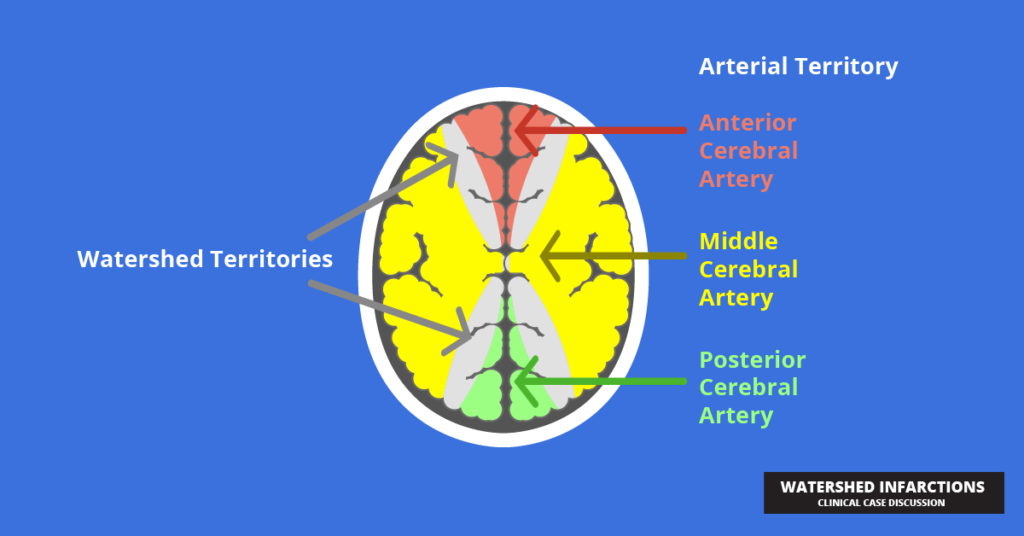

So, the watershed regions inside our brains are areas at the most distal points of our cerebral vascular territories; that is, they separate the cerebral circulation between areas. This means that they are the most vulnerable to infarction because they are on the border between two vascular supplies.

Because of this, watershed infarctions are also known as “Border zone infarctions”. With that bit of knowledge, let’s take a trip to the A & E, where we meet Mr. Harrison.

An elderly gentleman of 72 years, Mr. Harrison is a bachelor living alone at his apartment. He complained of a few episodes of right-sided weakness accompanied by some speech difficulties and slurring in the recent past. Other than this, he has suffered a fall and a few episodes of dizziness when standing up from seated position, which he says has prevailed for about a week. He has been a patient with long-standing diabetes mellitus and had been diagnosed with congestive cardiac failure by his local GP a week ago. For this, he had been prescribed with a combination of furosemide 40mg mane and captopril 12.5 mg three times a day. He is also on his regular dose of metformin, and his blood sugar has been well controlled. He smokes quite regularly, averaging to about 20 pack years, and engages in social drinking occasionally.

You may already have guessed that Mr. Harrison is suffering from a stroke, but it’s actually impossible to differentiate between other types of strokes and watershed infarcts based on the clinical features, which is why this is a radiological diagnosis. But before we get into that, it becomes necessary to explain how they occur.

Not the Same, yet not Another: Pathophysiology

Watershed infarcts may be diagnosed by high-end imaging techniques but their exact pathology remains controversial. However, what scientists seem to agree on is that they are a type of ischemic stroke occurring at the borders between territories of non-anastomosing vascular supplies. There are two proposed theories of occurrence:

- Low flow theory – meaning that they occur due to severe hypotension, conditions that alter the viscosity of blood (like sickle cell anemia) or significant arterial stenosis, lasting for more than a few minutes. Severe hypotension can occur in conditions such as cardiac failure and a reduced circulating blood volume (which may have been the case with Mr. Harrison) or in instances of cardiac arrest or even during cardiac surgery.

- Severe hypotension – usually produces bilateral lesions whereas

- Significant carotid stenosis – produces an ipsilateral lesion

- Micro emboli – these usually arise from inflamed atherosclerotic plaques and will lodge in major branches of the carotid vessels. Their clearance from the watershed zones is poor due to scanty perfusion.

Although these phenomena should theoretically affect any part of the brain, the watershed regions are the most vulnerable because of their unique vascular supply.

Watershed infarcts can be classified according to their anatomy as follows (heads up for a bit of anatomy recall!)

- External (cortical) border zone infarcts – they occur between the territories of the 3 main cerebral arteries of the circle of Willis (Anterior Cerebral Artery, Middle Cerebral Artery and Posterior Cerebral Artery). They appear as wedge-shaped infarcts in the superficial brain matter and are termed “Cortical Laminar Necrosis”

- Internal (deep) border zone infarcts – these occur between the three main vessels and the important end arteries such as the perforating medullary, lenticulostriate, recurrent artery of Heubner and the anterior choroidal arteries.

How would these Patients Present?

Mr. Harrison is a great example of a classic presentation of a patient with a watershed infarction. An elderly male patient with a number of comorbidities including diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and hypertension make sense because they accelerate dyslipidemia. Also, they may have significant modifiable risk factors such as a history of smoking and alcohol.

It is important to identify their presenting complaints. A useful mnemonic to remember this would be FAST, which represents Facial weakness, Arm weakness (called pronator drift), Slurring of speech, and Time to act (indicating the priority of intervention). These are essential features of any stroke. These patients are also at an increased risk of experiencing seizures compared to other stroke patients. Additionally, they may complain of weakness or numbness in their legs and loss of part of their visual field (hemianopia).

Their past medical history may include important clues as to the cause of this infarction, such as with Mr. Harrison. For example, he was diagnosed with congestive cardiac failure, which alone is a risk factor, but paired with the medication he was prescribed and his existing comorbidities, they form a lethal combination. We know that ACE inhibitors are an anti-hypertensive, whereas diuretics like furosemide will reduce the effective circulating volume. This adds up with his explanation of episodic postural hypotension from the time when he began taking his medication, and may very well have predisposed him to this unfortunate event. It may be important for you to inquire about medication like this, and exclude other risk factors based on the pathophysiology of the infarct, but only once the acute incident is managed and the patient has been stabilized. Initially, you may only have time to take a very basic history covering the key facts to aid in diagnosing and facilitating management.

Your Differentials

The first thing that should cross your mind would be an episode of hypoglycemia, which may also cause confusion and slurred speech and even motor weakness.

Other than that, we also think about

- Seizures

- A systemic infection or meningism

- Brain tumor

- Other toxic metabolic disorders excluding hypoglycemia – ex: hyponatremia

- Positional vertigo

On Examination

In general, it may be necessary to look for signs of systemic hypoperfusion such as tachycardia, low blood pressure, pallor and sweating. He may look clammy and confused, which confirms that this is indeed a medical emergency. He would also show signs of diffuse neurologic deterioration. The GCS will no doubt drop below the normal 15, and there may be impairment in memory and intellect too. Specific neurologic signs depend on the region where the infarct occurred.

A PCA-MCA watershed infarct will present with bilateral visual loss (we call this cortical blindness because the retina and visual pathways remain intact, but there is a problem at the visual cortex). Another complex pattern of visual loss known as “Balint’s syndrome” may also occur. On the other hand, infarcts in the ACA-MCA watershed region will present with proximal limb weakness (brachial diplegia) while sparing the face, hands and feet. This curious presentation is called “man in the barrel syndrome”. I know it may feel like you have your head stuck in a barrel hearing all of this, but this is exactly the opposite of a patient suffering from this syndrome!

How would You Investigate a Patient like This?

Yes, we did say that it is mandatory to have radiographic evidence to diagnose a watershed infarct, but it’s crucial not to get carried away with all the advanced imaging techniques modern medicine has to offer, and consider the patient as a whole.

First, it is important to realize that this is an emergency, because as the saying goes, time is brain! You simply do not have time to be looking for causes and proving hypotheses immediately. Therefore, we can categorize our investigations according to when we will be performing them.

Keep in mind that the objective of performing these investigations is to differentiate between a hemorrhagic stroke and an ischemic stroke (which will be crucial in our management) and narrow down a cause for the event to prevent a recurrence.

Thereby, the investigations we perform within an hour of presentation are:

- A CT scan of the brain (ideally, a diffusion-weighted MRI would show the earliest changes in ischemic strokes, but the availability and expense make this a limited choice.) If the CT changes are too subtle, we can try again in 24-48 hours

- Full blood count

- Clotting studies – especially if the patient is on any anticoagulants.

- Random blood sugar – crucial, as we MUST rule out hypoglycemia which is one of our most important differentials.

Further investigations which can be undertaken within 24 hours include:

- Routine blood tests – blood counts, platelet function tests, ESR

- Biochemical investigations – lipids and glucose

- ECG (to rule out cardiac pathologies, which are a common cause for watershed infarcts) and ideally a 24-hour ECG to exclude conditions like atrial fibrillation

- Carotid doppler – this is undertaken if we find an anterior circulation infarct, especially when a patient is fit for surgery.

In addition, we may delve into further investigations if we cannot find a cause, or if the patient is young. Some of these include,

- A CT or MR angiography

- Echocardiogram – ideally transesophageal echocardiography

- Vasculitis screen, antiphospholipid antibodies and a thrombophilia screen

- Rarely, we may even consider genetic studies

- Drug and tox screen

What would be Your Management Plan?

We have been reiterating the fact that any form of stroke is a medical emergency. And the quicker you treat, the better the prognosis. As the brain is compromised, we must maintain the patient’s airway, breathing, circulation and additionally, his blood pressure and swallowing reflexes.

Supportive therapy:

Obtaining IV access is essential as the patient cannot tolerate any oral drugs due to the risk of aspiration. If the patient is having seizures, we may need to administer buccal midazolam, or IV phenytoin.

Oxygen can be supplemented if the patient’s O2-sats drop below 95%, and if we suspect hypotension, we can administer IV fluids as well as vasopressors.

Thrombolysis:

Once we have excluded a hemorrhagic stroke, we are faced with the option of thrombolysis. For this, we must exclude any absolute or relative contraindications for thrombolysis which will not be specifically discussed here. The 4.5-hour window is more than just a window of opportunity, and may be the difference between life and death for these patients. The importance of thrombolysis is not necessarily to revascularize the already infarcted area, but rather to protect the penumbra and prevent the extension of the infarction.

The only thrombolytic given during an ischemic stroke is alteplase. Streptokinase is associated with an increase in the risk of death and intracranial hemorrhage and is therefore avoided in stroke patients. But thrombolytics come at the cost of many adverse effects, and we must be prepared to face an allergic reaction, anaphylaxis or angioedema as well as extracranial hemorrhage, and a stand-by crash-cart becomes essential.

Antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation:

A high dose of aspirin (300 mg) is given 24 hours after thrombolysis is carried out, or immediately if thrombolysis is contraindicated. This is continued for 2 weeks before it is switched to clopidogrel. Anticoagulants are not given to all patients, but specifically for those with atrial fibrillation 2 weeks after thrombolysis or those with arterial dissection or venous sinus and cortical vein thrombosis. The time-tested anticoagulant, Warfarin, is still popular in many settings because of its availability and low-cost, but it is increasingly being replaced by direct factor-Xa inhibitors such as Apixaban and Rivaroxaban which have far less side-effects and interactions although they remain extremely expensive.

Stroke Units

The patient must be admitted to a dedicated stroke unit and handled by a multi-disciplinary team to look into different aspects of care. They will be involved with assessing the patient’s swallowing function and for maintaining and monitoring thromboembolism prophylaxis. Additionally, this unit will look after the additional complications which occur following a stroke, which will be discussed in more detail in the upcoming section. They will also investigate for causes if a cause has not already been determined by this time and will provide early referral to a physiotherapist as well as an occupational and speech therapist to help with rehabilitation.

These stroke units will also function as clinics to follow-up patients and look into secondary preventive measures.

What are the secondary preventive measures?

Management of the patient’s comorbidities, both with pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic management, is of paramount importance.

Pharmacologic therapy:

- Antihypertensive therapy – although patients having Watershed infarcts commonly suffer from hypotension, they can be patients with a previous history of hypertension, and will have to be carefully treated ensuring that they do not relapse into episodes of hypotension. ACE inhibitors, ARBs and beta blockers can all be considered in these patients, but careful dose titration is needed.

- Treating dyslipidemia – can be treated with either moderate intensity statin therapy or with high intensity statin therapy, aiming for an LDL cholesterol level <70 mg/dl. Statins are also considered a necessary add-on therapy even for patients without dyslipidemia due to their pleiotropic effects.

- Glycemic control – It is important to control any transient elevations in blood sugar with insulin, and then convert back to the patient’s usual drugs. Sometimes, a change of medication is warranted if HbA1c levels rise beyond 6.5%.

Non-pharmacologic therapy:

- Stenting: In those patients with severe carotid artery stenosis, we opt for carotid endarterectomy because of the significant risk of recurrence of a stroke. This is usually performed about two weeks after the initial presentation, and a second imaging modality such as a CT angiography is used to aid the results of the Doppler studies. The requirement for carotid endarterectomy decreases steadily with decreasing severity of stenosis, and it is debatable whether it should be performed at all in patients with asymptomatic stenosis. In these patients, conservative management seems to be the safer approach.

- Life style modification: As with all non-communicable diseases, a significant proportion of the morbidity can be controlled with lifestyle interventions. Stroke patients must be educated about the importance of reaching their glycemic and blood pressure targets. These patients must be introduced to a low-salt diet, as it is the single most preventable risk factor for hypertension. Weight reduction and maintaining an optimum BMI with adequate physical exercise (at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise on 5 days of the week) must be recommended. Reducing alcohol and smoking is also important.

What Complications can We Expect?

Watershed infarcts, and all other forms of stroke are a debilitating disease which can leave patients bed-ridden and incapacitated.

This would cause the complications of prolonged bed rest such as,

- Orthostatic pneumonia – which requires chest physiotherapy and breathing exercises

- Pressure ulcers – needing grading and management, as well as frequently changing positions to avoid developing them

- Catheter associated infections and UTIs – bladder and bowel training must be begun early if the patient has lost control of these, and antibiotic prophylaxis may be considered.

- Fecal retention – stroke patients may sometimes need enemas

- Osteoporosis and disuse atrophy of muscles – the best way to handle this is by promoting active and passive exercises to regain lost function and minimize further deterioration.

- Psychological disturbances due to the sudden change in the way of living

Other than this, we may also be on the look-out for,

- Re-infarction

- Cerebral edema – an early complication occurring within 48 hours of the stroke

- Complications of thrombolysis – which have been discussed previously

Follow-up

In our case, it is important that Mr. Harrison is regularly followed up in the 2-3 weeks where he is taking antiplatelet therapy, and later at less frequent intervals for a period of at least 12 months. It is mandatory to ensure that his blood sugar control is good, and that he is reaching his blood pressure and triglyceride targets. His lifestyle modifications should be inquired into, as well as general living conditions, especially because he lives alone. An occupational therapist and regular support groups to help with rehabilitation and the cessation of smoking should also be considered.

References

Kumar & Clark’s Clinical Medicine – Edition 10 [Cited May 24, 2021]

Oxford Handbook of Acute Medicine [Cited May 24, 2021]

https://www.physio-pedia.com/Watershed_Stroke/Infarction

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watershed_stroke

https://radiopaedia.org/articles/watershed-cerebral-infarction

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/01.str.0000155727.82242.e1

https://radiopaedia.org/articles/man-in-the-barrel-syndrome