I’m hairy and scary and not meant to be,

I’ve got normal yet weird parts inside me,

Muscle and skin and more things to see,

Hair and bone and other debris.

What am I?

This creepy riddle refers to one of the strangest phenomena in human pathology – an anomaly that teased the brains of many a physician in the past, so much so that some of them, many years ago, finally claimed this to be the work of witchcraft, even though they were men of science. However, this set of beliefs which blamed the dark powers of the world belonged in the past, and now in modern medicine, this bizarre discovery is simply called – as is the answer to the rather unnerving riddle above – a teratoma.

Table of Contents

What are the components of teratoma?

Teratomas are extremely rare, and are a unique kind of neoplastic growth with features which easily distinguish it from other tumors.

Teratoma is a type of germ cell tumor. They are formed when neoplastic germ cells differentiate along many somatic cell lines. They end up forming firm masses, which contain tissues from all three germ cell layers with varying degrees of differentiation.

Within this type of tumor, often found are cysts and cartilage in addition to a multitude of other organic matter. Typically, teratomas have a composition of heterogenous, disordered mix of differentiated cells or even organoid structures, including:

- Neural tissues

- Brain matter

- Cartilage in small patches

- Squamous epithelium

- Bronchial epithelium

- Muscular elements

- Intestinal wall parts

- Thyroid gland–like structures

All of these fully developed tissues and organ structures are held together by a myxoid or fibrous stroma.

These elements which are found in teratomas may be:

- Mature – actually resembling different tissues which can be found in adult human bodies

- Immature – histologically closer to embryonic or fetal tissue

Teratomas can be found at all ages, since they may exist in an individual at any age, from infanthood to adulthood. But they are more common in infants and children, and less common in adults, especially in the case of pure teratomas.

Teratomas can even form during intrauterine fetal development.

These tumors have specific locations in which they are commonly found. Primarily, they are found in gonads, as well as along midline locations such as:

- Sacrum

- Coccyx

- Mediastinum – especially the anterior mediastinum

- Retroperitoneum

- Central nervous system – composed of the brain and spinal cord

Teratomas found in locations in the body other than the ovaries or testes are known as extragonadal teratomas.

Pathophysiology of Teratomas

Teratomas contain mature or immature cells derived from one or more of the three germ cell layers of the body – ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. Since these are pluripotent germ cells of the ovaries and the testes, they have the distinct and convenient ability to differentiate into almost any type of human cell found in the body. Thanks to this origination of teratomas from the gonadal cells which display pluripotency, they may end up containing elements such as:

- Bone

- Muscle

- Epithelium

- Fat

- Nerve tissue

- Nails

- Hair

- Teeth

The pathophysiology of formation of teratomas have a lot to do with their origins.

There is a theory in the scientific world encompassing teratomas and their origins, known as the Parthenogenic theory.

The Parthenogenic theory suggests that teratomas originate in primordial germ cells, as explained above. It explains why teratomas are found to initiate growth in the specific locations in the body which contain germ cells, such as the gonads. It also explains how the teratoma cells display features of pluripotency, with their potential to produce tissues very different to each other, like teeth, skin, hair, and wax.

Germ cells are undifferentiated cells, which is why many teratomas arise from sites containing these undifferentiated cell clusters.

Over stages of fetal development, only most of these germ cells develop to form the various tissues necessary to complete the structure and form of the fetus. Some remain in an undifferentiated state. These unchanged germ cells descend alone the midline, most storing themselves in the ovaries and testes until puberty, in order to form ova in females and sperm in males.

During pluripotent cell differentiation, if an error happens in the process, the now neoplastic cells end up differentiating into various random types of cells such as hair, bone, wax, sebum, skin or muscle.

What are the Types of Tearatomas?

Teratomas can be categorized according to the locations in which they arise. These subtypes of teratomas are:

- Ovarian teratomas

- Testicular teratomas

- Sacrococcygeal teratomas – extragonadal teratoma

- Mediastinal teratomas – relatively rarer

- Fetus in fetu – a type of teratoma found during intrauterine life in the fetal stages

- Other specialized teratomas – for example, Struma ovarii (a type of teratoma arising from formation and multiplication of thyroid cells)

Teratomas can also be divided on the basis of whether they are composed of mature cells or immature cells, which also involves the degree of differentiation of its tissues.

Mature teratomas – these are generally non-cancerous (benign), and may grow back even after surgical resection. They contain tissues which are fully developed. In children, these mature teratomas are normally benign, but in adults, there is a somewhat higher chance of malignancy. However, not all mature teratomas developing in adults follow this trend. For instance, mature ovarian teratomas are found in young adult females, but have little potential of malignant transformation. They are also the type of teratomas that have the greater chance of growing back after surgical resection.

Immature teratomas – Malignancy is more likely in this case, and with tendency of metastasis, as these teratomas contain undifferentiated tissues. Rarely, immature teratomas may contain constituents of somatic cancers like sarcomas or leukemias.

Mature teratomas can be further divided into:

- Solid mature teratomas – Composed of tissue, and not enclosed

- Cystic mature teratomas – Enclosed in a sac containing fluid

- Mixed mature teratomas – Contain both solid and cystic components

CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS OF TERATOMAS

Symptoms and signs of teratomas very depending on the type and location of teratoma, but there are certain features that are common, for example: pain, bleeding, and swelling at the site of the tumor.

Initially, teratomas may develop within the body with no clinical symptoms at all, and any discovery of early teratomas will be incidental.

Types depending on location:

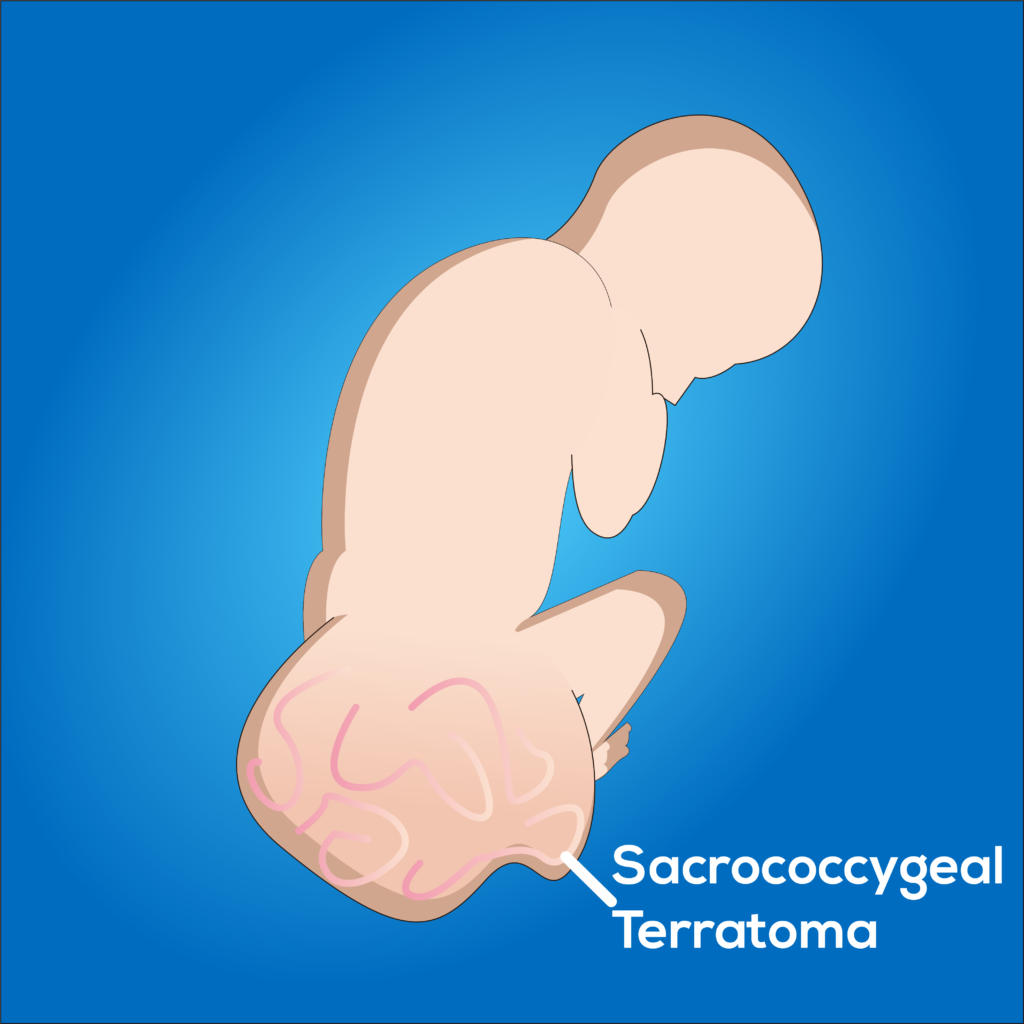

- Sacrococcygeal teratoma – most common teratoma in newborns

- Ovarian teratoma – most common ovarian germ cell tumor of reproductive age

- Testicular teratoma

SACROCOCCYGEAL TERATOMAS (Teratoma of the Tailbone)

Sacrococcygeal teratomas are the most common teratomas of childhood, accounting for more than 40% of childhood cases. About 10% of these teratoma cases are associated with congenital anomalies, such as defects of hindgut, defects of cloacal region, and defects along midline, especially anomalies like spina bifida and meningocele.

Even though this type of teratoma is the commonest tumor found in newborns and children, the teratoma by itself is quite rare. Statistics show that only 1 in 40000 infants are found to carry this type of sacrococcygeal tumor.

Among sacrococcygeal teratomas, the majority reaching almost 75% are mature and benign tumor growths. More than 13% are immature teratoma growths, and around 12% are malignant and potentially fatal.

Benign sacrococcygeal teratomas are usually found in infantile ages, that is, typically less than 4 months.

Malignant teratomas in the sacrococcygeal region arise in older children.

These may be visible sometimes, and are noticed by a parent or caretaker, but at times they may not be visible if they grow inside the body albeit still in close proximity to the tailbone. Among the cases diagnosed in the past years, teratoma of the tailbone may grow either inside or on the outside of the body, in the region of the sacrum and coccyx.

The presence of germ cells in the tailbone explains how teratomas can arise from the sacrococcygeal region.

They are more common in female infants or children than in males. The ratio obtained from a study done in 2015 on a group of patients treated for sacrococcygeal teratomas at a hospital in Thailand over the period between 1998 and 2012, was 4 to 1, with the bias towards female sex.

Symptoms of Sacrococcygeal Teratomas:

Besides the general symptoms of pain, swelling and bleeding at the site, sacrococcygeal teratoma growths – especially those which develop after birth – can also cause more specific signs and symptoms such as:

- A visible mass (detected on inspection of patient’s sacrococcygeal area)

- Abdominal pain

- Constipation

- Fecal incontinence – due to gastrointestinal tract obstruction

- Dysuria (pain while passing urine)

- Urinary incontinence – due to genitourinary tract obstruction

- Swelling in pubic region

- Progressive pain in lower back

- Weakness in lower limbs

- Edematous of proximal lower limbs

- Paresthesia and numbness of lower limb muscles – these are rare neurological symptoms

Diagnosis of Sacrococcygeal Teratomas:

When the size is larger, the teratoma can be detected via ultrasound scan of the fetus. It can also be found at birth. Obstetricians and pediatricians often examine neonates (newborns) to look for a swelling at the tailbone which could be suggestive of a sacrococcygeal teratoma.

Other diagnostic investigation options include: X-ray pelvis, CT scan (Computed Tomography scan), MRIs, and blood tests.

Management of Sacrococcygeal Teratomas:

Even benign teratomas need to be removed, because of their size and risk of further growth.

Rarely, in cases where sacrococcygeal teratomas are detected in intrauterine life, if the doctors monitoring the fetus believe the teratoma may cause complications, threatening the life of both the mother and the fetus, the teratoma may have to be removed as soon as possible via fetal surgery. A sacrococcygeal tumor which was discovered at birth are also removed via surgery done in the safest manner possible. Postoperative concerns include a need for close monitoring of the newborn because the chance of regrowth of the teratoma within the next 3 years is high.

OVARIAN TERATOMAS

They are most commonly found in reproductive age females; average – 30 years of age. Ovarian teratomas are rather rare in females over the age of 45.

Ovarian teratomas can be classified according to histologic appearance into 3 types:

- Monodermal teratomas – examples include: carcinoid tumors, neural tumors, struma ovarii (this specific type is also classified under specialized teratoma subtypes)

- Immature teratomas

- Mature cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts)

Most ovarian teratomas are mature. Immature teratomas, while being significantly scarcer, are found mostly in young females who are less than 20 years of age.

As much as 98% of ovarian teratomas are benign, with only about 2% having malignant potential.

An ovarian teratoma may vary in size – its diameter may be any length from 0.5 inches to even greater than 17 inches.

Immature ovarian teratomas are commonly detected at adolescence (mean age of 18 years). These can be bulky and solid masses, often containing patches of necrotic tissue. Rarely, they may contain cystic foci with hair, sebaceous fluid, and so on, but these features belong more in mature categories of teratomas.

Mature cystic teratomas (also called dermoid cysts) are the commonest of 20% of ovarian germ cell tumors. They have a slow growth rate of approximately 1.8 millimeters per year. Risk factors of this type of ovarian teratomas include: alcohol abuse, late menarche and irregular menstruation, past history of cystic teratomas, infertility and fewer pregnancies.

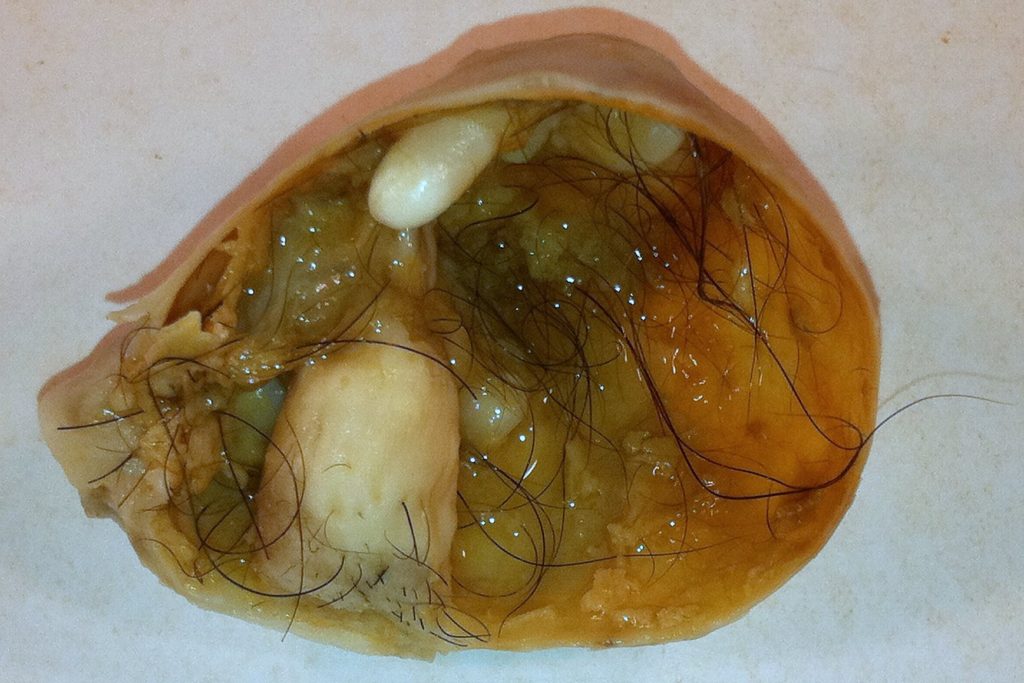

Benign mature cystic teratomas characteristically have mature tissues derived from all three germ cell layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm). They contain cysts lined by epidermal cells – the so-called dermoid cysts.

Mature ovarian teratomas have been known to be asymptomatic.

Symptoms of Ovarian Teratomas:

When the teratoma growth is capable of causing clinical manifestations:

- Severe abdominal pain

- Severe pelvic pain – radiates upwards – may be due to ovarian torsion caused by teratoma mass

Investigations for Ovarian Teratomas:

X-ray scans, ultrasound scans, MRIs, CT scans, bone scans – these are used to locate the teratoma, and to assess spread and pinpoint any local or distant metastasis.

Biopsy is necessary to assess malignancy of the teratoma.

Blood investigations are used in cases of paraneoplastic teratomas which can be detected via changes in specific hormone levels in blood.

Diagnosis of Ovarian Teratomas:

These are difficult to diagnose, almost all ovarian teratomas are found accidentally upon performing routine gynecological investigations for female health. They may initially be diagnosed as an ovarian mass.

It can also be mistaken for a cyst, therefore, taking the patient’s history, especially her symptoms and their progression, is necessary.

After surgical resection of cystic teratomas, a cut section of the extracted teratoma may contain sebaceous secretions and matter hair – closer examination may reveal it to have a hair-bearing epidermal cell lining. In some cases, teeth may protrude from nodular projections. It is likely to also contain other expected components of teratoma growths, for example, bone, cartilage, bronchial epithelial cells, gastrointestinal epithelial cells, etc.

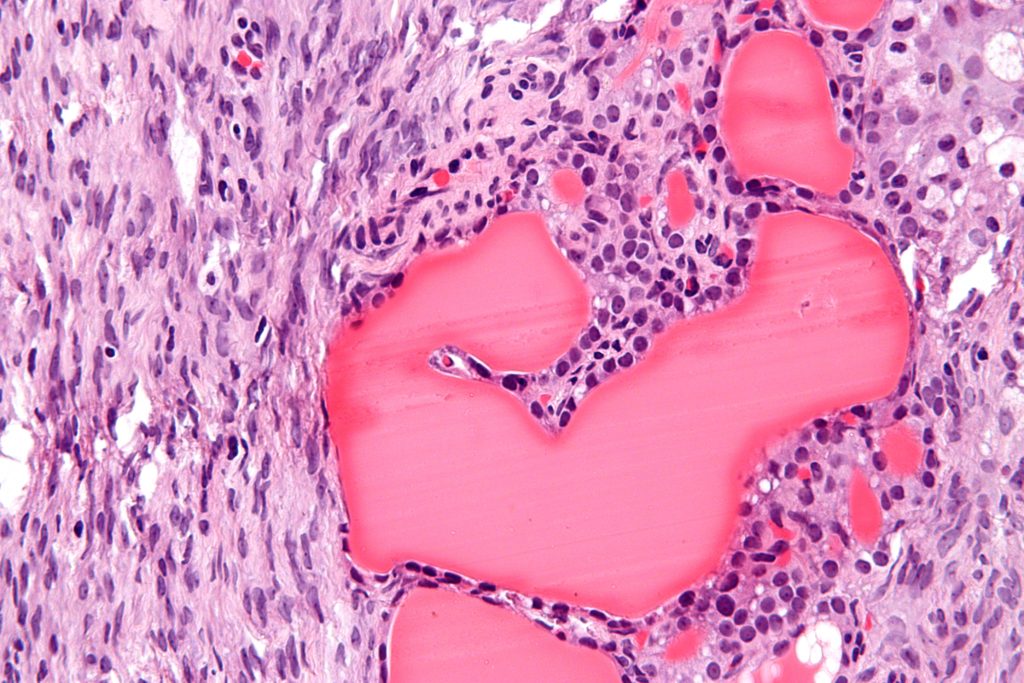

Examination of a resected immature teratoma under microscope may reveal immature elements and minimally differentiated elements such as bone, muscle, nerve, and cartilaginous tissue.

Complications of Ovarian Teratomas:

With increasing size, ovarian teratomas can cause pressure symptoms in the ovary, possibly even leading to the disruption of blood supply to ovary (ovarian torsion).

Rarely, this type of teratoma is associated with NMDAr-encephalitis, which is a type of limbic encephalitis – a paraneoplastic complication seen especially with teratomas whose composition include mature neural tissue. This causes both neurological symptoms such as severe headaches, and psychiatric symptoms which include confusion, hallucinations, and altered consciousness. Fortunately, recovery and ablation of these symptoms is possible after surgical resection of the teratoma.

Ovarian teratomas are also associated with syndrome of rapid onset psychosis, epilepsy, catatonia, and coma.

In 25% of cases, both the ovaries will contain dermoid cysts (mature cystic ovarian teratomas), which carries a high risk of decreased fertility or total infertility.

Ovarian cystic teratomas carry the risk of infection, rupture, and adhesion formation. Rupture of a cystic ovarian teratoma will require urgent laparotomy.

Malignant transformation is a risk in just 1% of cases.

An extremely rare complication that has been associated with immature ovarian teratomas is Gliomatosis Peritonei. In this condition, benign mature glial tissue gets implanted within the peritoneum. According to research done on its genetic aspect, specifically the exome sequence, it has been discovered that this process of gliomatosis is genetically similar to the ovarian teratoma as it develops from the dispersed cells of the initial ovarian teratoma.

Risk factors which increase chance of malignant transformation of ovarian teratomas:

- Older age – especially post-menopausal ages

- Large tumor size

- Increased levels of CA-125

Management of Ovarian Teratomas:

Mature ovarian teratomas are removed via laparoscopic surgery, if the cyst is small. Small abdominal incisions are made for the insertion of the laparoscope as well as other necessary surgical instruments.

Laparoscopic surgery itself may pose a risk if the cyst is accidentally punctured during extraction, causing leakage of waxy substance from within the cyst. These leaked contents can induce an inflammatory response, even leading to chemical peritonitis.

Sometimes, the ovary containing the teratoma will have to be partially or totally removed. In such a case, the remaining ovary has to manage ovulation and menstruation in the female.

However, even if there is a delay in diagnosis, especially in cases of immature ovarian teratomas, teratomas diagnosed at advanced stages can usually be cured successfully be surgery and chemotherapy.

TESTICULAR TERATOMAS

Testicular teratomas is the second most common germ cell tumor in males. They account for approximately 4 to 9% of all testicular tumors. Teratomas of the testes grow rapidly.

Testicular teratomas may be diagnosed in two age groups – pre-pubertal age group (which is the pediatric age group) and the post-pubertal age group (which is the adult group). Pre-pubertal teratomas are usually mature and non-cancerous, but post-pubertal ones can be malignant. A proportion of about two thirds of males with adult or post-pubertal teratoma diagnosis show advanced stage of metastasis.

Common age of diagnosis of adult teratomas is between 20 and 30 years of age.

Symptoms of Testicular Teratomas:

- Testicular lump or swelling

- Pain in testicular swelling – this is a symptom that may be common to both benign and malignant testicular teratomas.

Some may have no symptoms at all, especially over the initial stages. They can sometimes present simply as painless lumps in the testes.

Investigations for Testicular Teratomas:

Blood tests – may show elevated levels of serum beta-hCG (beta-human chorionic gonadotropin – a type of tumor marker), or mildly elevated serum AFP (Alpha Fetoprotein – also a type of tumor marker, especially for immature teratomas) levels.

Ultrasound scans – to help determine the rate of teratoma development

On genital examination specifically focused on the testes, atrophy of the testes may be detected. The mass, when palpated, may feel firm, in which case the possibility of malignancy must be considered.

Diagnosis of Testicular Teratomas:

These teratomas are usually discovered by accident, similar to other types of teratomas.

Management of Testicular Teratomas:

If the testicular teratoma is malignant, the first line treatment is total removal of the teratoma growth via surgery. Chemotherapy is not very effective in these cases. However, in cases of mixed tissue growths – for example, teratoma tissue and other cancerous tissue, chemotherapy may be necessary.

Complications of Testicular Teratomas:

Testicular torsion is a common complication which can occur as the teratoma grows in size.

There are also complications that may arise as a result of treatment, specifically, surgical removal. If the whole testicle is removed in order to get rid of the entirety of the teratoma, the patient should be warned and advised about the consequential effects he may have to face after the surgery, such as effects on fertility, sperm count, and other aspects of sexual health.

Risk Factors for Testicular Teratomas:

- Advanced maternal age – mother having been over 35 years of age at the time of giving birth to the affected baby boy

- Low birth weight

- Cryptorchidism – undescended testes; one or both of the testes having failed to descend into scrotum

- Hypospadias – a congenital anomaly in which the opening of the urethra is on the underside of the penis instead of its normal location at the tip of the penis.

OTHER TYPES OF TERATOMAS

Mediastinal teratomas

These teratomas are usually benign and are most commonly found in the anterior mediastinum. Its symptoms mainly stem from the effects of any pressure it may exert on surrounding structures. If the size of this teratoma growth is significantly large, it may affect breathing and cardiac function.

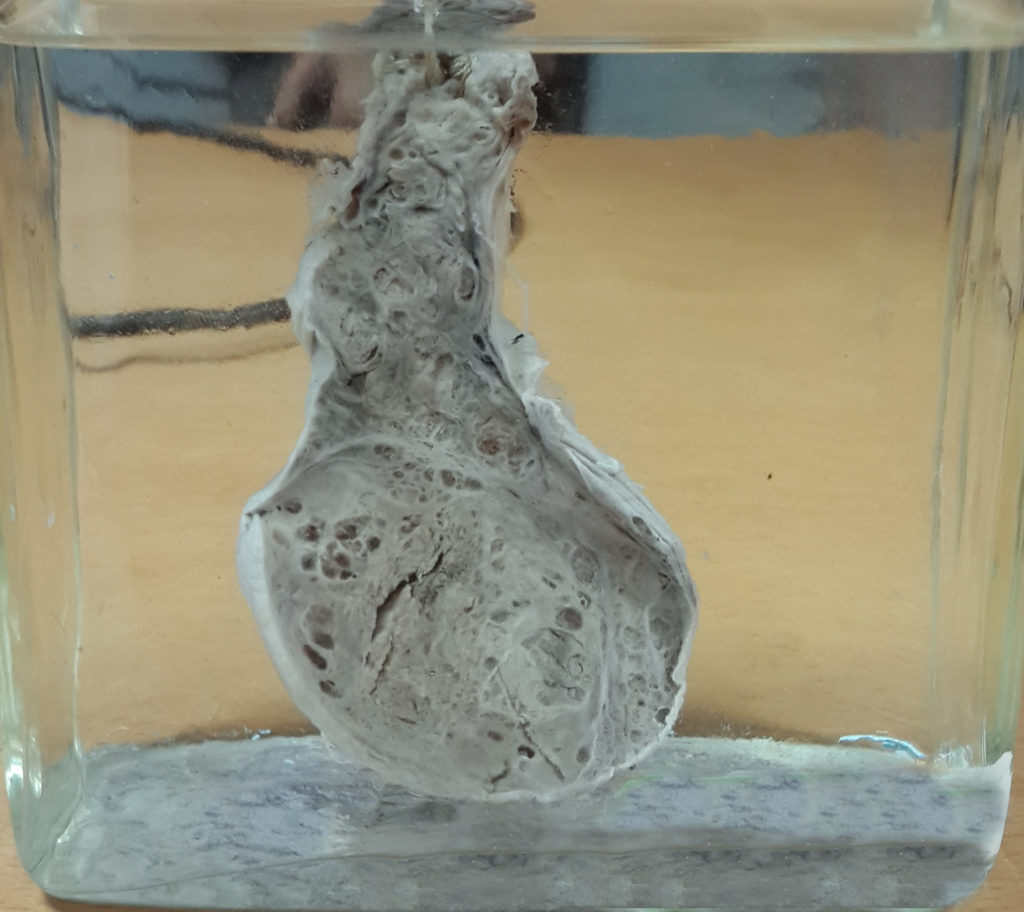

Fetus In Fetu

Fetus in fetu means: ‘Fetus within a fetus’.

They are found in MCDA (Mono Chorionic Diamniotic) twins – that is, twins who have their own amniotic sac but share one placenta.

These types of teratomas are quite rare, with an incidence of 1:500,000 fetuses. The majority of these tumors (more than 90% of them) are found within the first 18 months of life. Recorded cases show no bias towards male or female sex.

Made of living tissue, they resemble tiny malformed fetuses, but there is no chance for any true fetal development, since it has no amniotic sac or a placenta for nourishment. It is conjectured that these teratomas are remains of a twin which had failed to develop, and ended up being engulfed by the other surviving twin in the uterus.

Another theory exists, speculating that fetus-in-fetu teratomas are dermoid cysts which have developed further, as in this context, a dermoid cyst is a benign collection of different types of tissue (such as: hair, teeth, fluid, skin components) arising beneath an infant’s skin, regarded as a developmental anomaly.

However, the first theory is thought to have more of a basis, considering the extent of development of the teratoma. Most of them do not have a brain structure, but 91% of them have a spinal column, and 82.5% of them have limb buds.

In cases of fetus-in-fetu, it’s possible with the help of advanced imaging techniques, to detect and diagnose teratomas as early as in intrauterine life. As the fetus develops along with the teratoma, careful monitoring and special attention is advisable for the duration of the pregnancy.

The mode of delivery of the normal and viable fetus can be decided depending on the size of the teratoma. Teratomas of smaller size are less cause for concern, therefore normal vaginal delivery is safe. Teratomas of larger sizes may need the fetus to be delivered pre-term via a lower segment Cesarean section. If a teratoma exists along with a polyhydramnios state (having an excess of amniotic fluid within the amniotic sac), an early lower segment Cesarean section is once again advisable. In rare cases, surgery involving the fetus maybe required to prevent dangerous complications by removing the teratoma.

Teratomas of Head and Neck

These are much less common and mostly include teratomas on skull sutures, on scalp, and even in the nasopharynx.

Struma Ovarii

This subtype of specialized teratoma contains only mature (functional) thyroid tissue, and may even be capable of causing thyrotoxicosis in the patient if it produces T3 and T4, although this is not commonly seen. This teratoma manifests as a small, solid, brown mass in unilateral ovaries.

COMPLICATIONS OF TERATOMAS

General complications common to teratomas in most locations of the body:

- If the teratoma is hormone-secreting, in children, it can cause obvious secondary sexual characteristics at pre-pubescent ages, as it leads to precocious puberty (early onset puberty).

- If it the teratoma develops in intrauterine life, its high demand of blood within the fetus poses a risk of heart failure in the fetus, which may potentially lead to a condition known as hydrops fetalis (accumulation of fluid in the fetus) which in turn may lead to intrauterine death of the fetus.

PROGRESSION OF TERATOMAS

Specific subtypes of teratomas have different rates of growth, and varying malignant potential.

Some remain benign for the entire duration of their existence within the body. Some teratomas have an increasingly higher risk of malignant transformation the longer they exist inside the body.

INVESTIGATIONS FOR TERATOMAS

Blood, radiological, and histopathological investigations common to most types of teratomas include:

- Blood tests – to look for tumor markers, relevant hormone levels

- X-rays and CT (Computed Tomography) scans of chest, abdomen, etc. – to check for metastasis

Some developed teratomas located within the body may be incidentally discovered on abdominal scans – what is detected will be the small concentrated areas of calcification associated with the toothlike structures within the tumor cell cluster – at least in those teratomas which do contain teeth.

- Tissue biopsy – needed to confirm diagnosis

The maturity of teratomas can be observed from the biopsy specimen. Mature teratomas have high histological variation while immature teratomas have more primitive histology. Malignancy of the discovered teratoma can also be evaluated via biopsy.

- Other investigations which can also be done to assess the health of the patient if necessary are lung, liver, and kidney function tests, especially in cases of advanced malignant teratomas.

DIAGNOSIS OF TERATOMAS

Diagnosis depends on where the teratoma is located – in one of the several germ cell-containing areas in the body.

A thorough history taking and careful examination of the relevant region can help in preliminary diagnosis.

Once the growth has been diagnosed as a teratoma, staging is performed to assess the growth and spread of teratoma and thereby decide on the course of action to treat it.

Stage 1 teratomas are usually small and localized, whereas stage 4 teratomas are larger with evidence of spread – distant metastases.

TREATMENT OF TERATOMAS

Treatment of teratomas depend on the size and location of the tumorous growth, as well as its malignant transformation probability.

Treatment may also vary depending on factors such as age of patient, and health of patient. It is necessary to assess fitness of patient for surgery and also consider the health condition of the patient to withstand chemotherapy.

Teratomas, especially of the malignant and metastasizing varieties, require surgery. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are also recommended to reduce size of the primary tumor as well as to remove metastatic lesions.

Chemotherapy following surgery is especially necessary for immature ovarian teratomas as well as testicular teratomas.

On the other hand, some small and asymptomatic teratomas which are confirmed to be benign will not require patient to immediately undergo surgery to excise the teratoma especially when it has no effects on surrounding tissues currently and in the near future as well. Instead the patient will first be monitored and advised to return for regular follow-ups, to ensure the growth has not turned cancerous.

PROGNOSIS OF TERATOMAS

The survival rate of most teratomas are good, especially with early diagnosis and management. If the teratoma is found to be malignant, the prognosis will depend on its grade and stage, similar to most tumor growths. With a combination of surgery and chemotherapy, even most malignant teratomas can have very good survival rates.

Some varieties of teratoma have been known to carry risk of recurrence. For example, benign cystic teratomas have very good prognosis after surgery, but they have a risk of recurrence within the next 2-10 years.

ETYMOLOGY

The word ‘teratoma’ originated from the Greek word τέρας – which is read as “téras”, meaning ‘monster’. This word was presumably used to name teratomas since they contain a rather rare and implausible jumble of cells and tissue, all different to one another, and were initially impossible to explain on a scientific basis.

DID YOU KNOW?

Back in the days when little to nothing was known about the phenomenon of teratoma growths, beliefs ranged from religious to ridiculous. For instance, patients who were found to have developed teratomas were thought to either be receiving punishment for cannibalism – implying that the patient had actually swallowed body parts which made up the teratoma, or being affected by a curse which was responsible for creating the unnatural collection of natural human parts.

Teratomas have also become useful in research to help discover properties of germ cells and embryonic stem cells.

SUMMARY

Teratomas are rather grotesque collections of cells and tissues found in various areas of the body containing germ cells. They arise from these pluripotent germ cells and therefore possess the ability to differentiate into various types of calls, ranging from hair to wax to bone to cartilage to skin. These growths can be either benign or malignant, and the tissues within the teratoma may be immature or mature in extent of differentiation. The commonest types of teratomas are ovarian teratomas, testicular teratomas and sacrococcygeal teratomas. They are the most unique type of cancerous growths in the body, since their cells are not limited to one type of tissue. Diagnostic investigations for teratomas include blood and radiological tests. Treatment includes surgical excision and chemotherapy to ensure that any metastases is taken care of.

Teratomas have been regarded as a frightful medical phenomenon especially in the past, but it has also been found to be beneficial in histological research.

Even though the development of a teratoma may come across as rather alarming especially in very young children, timely management leads to good prognosis.

REFERENCES

https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/teratomas

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22074-teratoma

https://www.healthline.com/health/teratoma

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/teratoma

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564325/

https://www.osmosis.org/answers/teratoma

https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/what-is-teratoma

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teratoma

https://serendipstudio.org/exchange/priscila-roney/teratoma-monster-may-lead-cure

Robbins Basic Pathology 10E

Fundamentals of Pathology 2018 Edition